Neanderthals as Artists? The Discovery of Ancient Crayons Sparks a Debate About Human Evolution and Creativity in Prehistoric Times.

The recent discovery of ocher artifacts in ancient rock shelters in Ukraine has sent waves through the archaeological community, challenging preconceptions about Neanderthals and their capacity for creativity. Two chunks of ocher, dating back 47,000 and 46,000 years, appear to have been intentionally shaped into crayons, revealing that our prehistoric cousins were not just primitive beings but potentially possessed an artistic sensibility that parallels human creativity.

The ocher artifacts were found in Zaskalnaya V, a site that was one of the many rock shelters used by Neanderthals, which once sprawled across the landscape near modern-day Bilohirsk, Crimea. These shelters, occupied between 100,000 and 33,000 years ago, have become crucial in our understanding of Neanderthal life, culture, and innovation. The ocher in question is an iron-rich mineral that can yield a spectrum of colors—from red to yellow to orange. Historically, ocher has been used for various purposes, including as a pigment for cave paintings, in rituals, and for practical applications like tanning animal hides or creating adhesives.

What sets these particular pieces apart from most ocher finds are the marks they bear. Researchers employed advanced techniques such as X-ray fluorescence and scanning electron microscopy to analyze 16 chunks of ocher. They discovered that the two crayons showed signs of deliberate shaping and regular resharpening over time, indicating they were likely used for drawing or painting. A third piece had been meticulously carved with parallel lines, further suggesting artistic intent.

These findings ignite a profound debate about the cognitive abilities of Neanderthals. Historically, there has been a tendency to perceive Neanderthals as lesser beings compared to Homo sapiens. This perception was rooted in a belief that they lacked the same level of intelligence and cultural sophistication. However, the evidence of ocher crayons challenges such stereotypes. If Neanderthals were indeed capable of producing objects for artistic expression, it prompts a reevaluation of their place in the evolutionary narrative. Were they simply another branch of the human family tree, or did they possess unique aspects of culture that were systematically undermined by the prevailing Homo sapiens narrative?

The implications of this discovery extend beyond the artifacts themselves. It raises questions about what it means to be human, the development of artistic expression, and the origins of cultural practices that we often attribute solely to modern humans. The notion that Neanderthals created tools for art aligns with the overarching view that creativity is an inherent aspect of the human experience, not exclusive to Homo sapiens.

This discovery is not an isolated incident in the ongoing exploration of Neanderthal life. Numerous studies over the years have unearthed evidence that suggests Neanderthals had complex social structures, utilized tools with sophistication, and even engaged in burial practices, which indicate an awareness of mortality and possibly an understanding of the spiritual realm. The artistic use of ocher fits neatly into a growing body of evidence that suggests the capacity for symbolic thought and creativity might not be unique to modern humans.

Much of the recent exploration into Neanderthal life has been driven by advancements in archaeological techniques and a more nuanced understanding of what it means to be human. As researchers continue to uncover artifacts from the past, our understanding of Neanderthals is evolving, and combined with genetics and paleogenomics, which allow scientists to study ancient DNA, an intricate picture of our extinct relatives is emerging. Genetic studies have shown that Neanderthals interbred with early modern humans, which means that contemporary humans carry traces of Neanderthal DNA, further complicating the narrative of human evolution.

The ocher crayons found in Ukraine may only be the tip of the iceberg. As exploration into Neanderthal cultural practices continues, it is likely that more evidence will surface that could further illuminate their competency in creative endeavors. It is also possible that these discoveries will lead to reexaminations of various historical and prehistoric narratives.

Archaeologists and anthropologists are grappling with the implications of these findings. Should we begin to regard Neanderthals as artists rather than mere survivalists? The answer is likely to be contentious, with some experts advocating for a complete reevaluation of Neanderthal capabilities. The artistic use of ocher suggests that they were not just focused on survival but may have had a rich cultural life that included self-expression, creativity, and perhaps even emotional depth.

The debate surrounding the artistic inclinations of Neanderthals also ties into larger themes within contemporary society, encompassing discussions about cultural heritage, identity, and the importance of recognizing diverse forms of expression. It calls into question our definitions of what it means to create art and how we classify cultural achievements. Just as the study of Neanderthals is breaking down the rigid barriers that have historically separated us from them, it is prompting us to reconsider cultural hierarchies and the ways in which we appreciate the contributions of various cultures to the tapestry of human history.

The ongoing analysis of these ocher crayon artifacts from the Crimean rock shelters is just one facet of the broader narrative we are beginning to piece together about Neanderthal life. Each discovery provides more context to their existence, propelling researchers into discussions about their society, interactions, and what it means to be a member of the human lineage. As our understanding of Neanderthal culture evolves, so too does our comprehension of our ancestry and shared heritage.

The implications of such findings have the potential to reshape educational curriculums, museum exhibits, and public discussions about human evolution and the real significance of Neanderthals in our history. The narrative may shift from one of extinction and survival to one of a vibrant, creative community that existed long before the modern human era, effectively bridging the gap between the past and present.

As we continue to uncover the layers of Neanderthal life, we can only speculate about the stories these ancient crayons could tell. What did the Neanderthals seek to express with their ocher? Did they draw the animals that populated their environment, create patterns with symbolic meaning, or perhaps engage in storytelling through illustrations? Each new piece of evidence invites us to expand our imagination and look more deeply into the capacities of our ancient relatives, especially as they now appear to share a common thread of creativity with us, the modern humans who populate the Earth today.

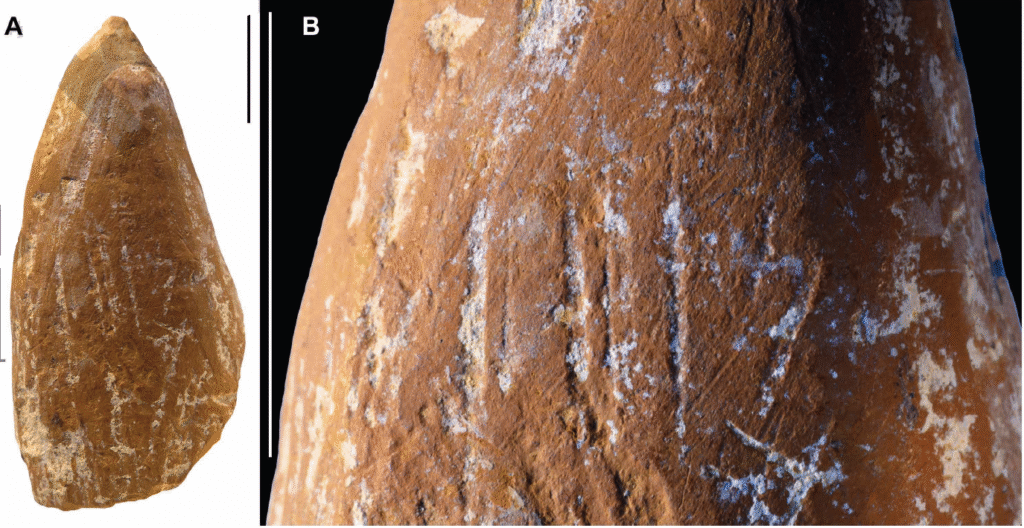

Two chunks of ocher unearthed at ancient rock shelters in Ukraine were actually Neanderthal crayons, according to a recent study. The pair of artifacts, unearthed from layers 47,000 and 46,000 years old, showed signs of being deliberately shaped into crayons and resharpened over time. A third piece of ocher had been carefully carved with parallel lines. The finds add to the growing body of evidence that Neanderthals had an artistic streak.

This piece of yellow ocher was used as a crayon and resharpened before finally being worn blunt and discarded.

Credit:

D’Errico et al. 2025

Please pass Og the yellow crayon

Rock shelters, occupied by Neanderthals between 100,000 and 33,000 years ago, dot the landscape near the modern city of Bilohirsk in Crimea (a peninsula in southern Ukraine). Archaeologists studying those rock shelters have unearthed dozens of chunks of an iron-rich mineral called ocher. Many of them have flakes knocked out or grooves gouged into their surface, which mark how Neanderthals extracted powdery red, orange, or yellow pigment from the stone. D’Errico and his colleagues used X-ray fluorescence and scanning electron microscopes to examine 16 ocher chunks to better understand exactly what ancient Crimean Neanderthals were doing with the stuff.

Most of those ocher chunks could have been used for nearly anything. Ocher is handy not just as a pigment but also for tanning animal hides, mixing with resins into adhesives for hafting tools, or even repelling insects and preventing infection. Knapping a few flakes off a hard nodule of ocher, then crushing them into powder (or just carving out a chunk of a softer, more crumbly piece), is a good way to prepare it for any of those uses. But two pieces, both from a site called Zaskalnaya V, were clearly different.